Journalism Safety - Research report

Online harms against women working in journalism and media - Research report 2023

This report has been produced by Women in Journalism and Reach plc following collaborative research conducted in February 2023. Research and report authored by Dr Rebecca Whittington.

Project team:

Alison Phillips (Chair of Women in Journalism and Editor-in-Chief of the Mirror)

Dr Julie Humphreys (Head of Diversity & Inclusion, Reach plc), Alison Gow (Co-chair of Reach Equality - gender inclusion network at Reach plc - and committee member for Women in Journalism) Dr Rebecca Whittington (Online Safety Editor and Co-chair of Reach Equality - gender inclusion network at Reach plc - and committee member for Women in Journalism)

Emily Nagy (Diversity & Inclusion Manager, Reach plc)

Um-E-Aymen Barbar (Committee member for Women in Journalism) Lija Kresowaty (Head of External Communications, Reach plc)

This report was published on March 8, 2023, to coincide with International Women’s Day. The report images and information is copyright of Reach Plc and Women in Journalism.

Contents

Message from Alison Phillips 5 Introduction 7 The key statistics 8 Headline findings 9 Key themes 10 Call to action 11 Support by Women in Journalism 11 Questionnaire results 12

Personal situation 12 Figure 1. Participants’ employment status 12 Figure 2. Participants’ main type of work. 13 Figure 3. The public visibility of participants 14 Figure 4. How long participants have worked in journalism or media. 14

Personal experience 15 Figure 5. Perceptions of threat to safety during work 15 Figure 6. Perceptions of threat to safety during work in the past 12 months 16 Figure 7. Categories of harm experienced overall 16 Figure 8. Categories of harm experienced in the past 12 months 17

Testimony: threats to safety online and in person 17 Figure 9. Harms connected to personal characteristics 18 Testimony: Attacks on personal characteristics 19

Platforms for abuse 19 Figure 10. Platforms reported overall 20 Figure 11. Platforms reported in the past 12 months 21

Support and response 21 Figure 12. Support sought by participants in the event of online harm. 22 Figure 13. Police response in the event of a report. 23

Testimony: Police report and response 23 Figure 14. Confidence in company response/support - all participants 24 Figure 15. Confidence in company response/support - freelance and temporary contract participants 25 Figure 16. Confidence in line manager response/support 25 Figure 17. Confidence in line manager response/support - freelance and temporary contract participants 26 Figure 18. Confidence in how to take action or find help in the event of online harm in the future. 26

Figure 19. Confidence in what support to seek or action to take - freelance and temporary contract participants 27 Testimony: Support from companies, managers and confidence in knowing what to do and where to find help in the future 27

The impact of the threat of online harms on participants’ professional practice 28

Figure 20. Impact of online harms on participants’ professional practice 29 Testimony: The impact on participants’ professional practice 30

Summary and recommendations 31 Support options 33 Acknowledgements 33

Message from Alison Phillips

Chair of Women in Journalism and Editor-in-Chief of the Mirror

Over recent decades we have seen an encouraging growth in the number of women entering journalism - and sticking with it. We now have women working - and reaching the top - in most areas of the industry.

But serious challenges do remain. Particularly for women who are Black, from another ethnic minority background or who have a disability, who are still underrepresented.Women in Journalism is determined the barriers to career progression must be broken down to ensure women’s voices are more clearly heard in the national conversation.

But beyond the systemic challenges facing women we have grown increasingly conscious in recent years of a newer, sinister attempt to silence women journalists - the growth of online abuse. Our members told us how they and colleagues had been deeply shaken, often frightened, by online trolling, pile-ones and vicious personal attacks. Some said it was making them avoid reporting on certain stories or less likely to promote their work on social media platforms. I heard of one reporter who no longer wanted her byline used. This seemed to us a deeply troubling situation. Both for women journalists who must be able to pursue their careers however they wish. And also for a healthy democracy which requires the voices of all to be heard - which means a diverse media equipped to tell those stories.

It was this which prompted Women in Journalism to collaborate on this report with the publisher Reach, which is leading the way in best practice on this issue. We wanted to discover if data backed up the anecdotal evidence we had been hearing. The results in this report tragically prove it does.

Women in Journalism now calls on editors and publishers to consider this report and act swiftly upon its recommendations to protect all its journalists subject to online abuse - particularly women, and those who are Black, from another ethnic minority background or have a disability.

Women have fought a long and hard battle to be seen and heard in journalism. We now have a new fight - against those who try to silence us with online abuse and ridicule. But we refuse to be silenced - because what we do is too important.

Join us in ending the abuse which - as proved by this research - has become ‘the norm’ for women working in journalism. Abuse is not normal and should not be accepted. Today we call for action to #StopSilencingWomenJournos

Alison Phillips

March 8, 2023

Introduction

When Women in Journalism and Reach met for the first time to discuss a collaborative project to hinge around International Women’s Day 2023, there was only one subject on the table - the online abuse of women working in journalism and connected industries and its impact on the diversity of voice and representation of women.

Anecdotally, there is a multitude of evidence to suggest online harm(1) against journalists - including harassment, abuse, malicious messaging and more - has increased since the Covid-19 pandemic(2).

There has also been some research conducted to assess the impact on a global scale - research by UNESCO(3)demonstrated in 2020 that high numbers of women journalists were being silenced by online violence conducted against them. In the same year in the UK, there was research conducted by the National Union of Journalists(4) which demonstrated a safety problem facing journalists across industry and which prompted the creation of the NUJ’s excellent Journalists’ Safety Toolkit(5).

However, until this point, there has not been a deep-dive into the situation for women working in the UK or an assessment of the impacts such online harm has on the careers and mental health of those affected. With this research we wanted to investigate the situation and find out what the impacts of online harm were on the women producing the news and journalistic content in the UK. We also wanted to use our privileged position as the UK’s largest commercial publisher and an organisation established to amplify the voices and opportunities of women working in journalism in the UK, to call for publishers and broadcasters to take collaborative action.

The questionnaire was distributed via social media and email for a three week period. More than 400 women, non-binary and those who preferred to self-describe completed the questionnaire - each one identifying as a journalist or working in media More than a third of those participants also offered written examples of their experiences.

There were also completions from male participants, often offering their allyship to women - these responses were removed prior to analysis but have been retained for potential use at a later point.

Thank you to all of those who participated, amplified, shared and championed the research. The final completion rates were testimony to the importance of the subject under investigation.

This report will go on to highlight the main stats, the headline findings, key themes and a subsequent call to action for publishers and broadcasters, plus the support pledged by Women in Journalism to facilitate the action. A breakdown of the survey findings is also available.

There are some themes in this report which readers may find upsetting. Please see the end of the report for contacts which can offer support.

For questions about the research , findings or more information email rebecca.whittington@reachplc.com

The key statistics

The survey received more than 410 responses in total.

Of that number:

● 97.8% of respondents were female

● 1.5% preferred to self-describe

● 0.7% identified as non-binary

● 13 men completed the survey

Analysis was based on 403 responses following removal of male participants

Headline findings

● 75% of participants said they had experienced a threat or challenge to their safety from a member of the public online, in person or online and in person during the course of their work.

● A quarter of participants said they had experienced some kind of sexual harassment or sexual violence in connection to their work.

● Almost a fifth of respondents said the threat of online harm had made them consider leaving the media industry.

● Almost half said they promoted their work less online due to the threat of online harm.

● Only a third of freelance participants expressed confidence in finding help or knowing what to do in the case of experiencing online harm. Confidence rose to more than 60% in participants employed on permanent contracts.

Other key findings

● A fifth of respondents said they had been subjected to harassment, sustained abuse or stalking in connection to their work.

● Hate speech, backlash or pile-on and personal comments were the most reported issues from the past year.

● More than a third reported being threatened or intimidated face-to-face at some point during their career.

● Almost half of respondents said they had experienced misogynistic harms or harm connected to their gender or gender identity.

● Reported harms were intersectional; 7% said harms experienced were connected to ethnicity, 7% said nationality had been a factor and 7% said harms experienced had been connected to socio-economic status or background.

Key themes

● The challenges of addressing harassment, long-term abuse or stalking were raised multiple times. Participants’ examples suggested an inconsistency in response from employers and police.

● The mental health impacts of online harm was referenced regularly, with some participants sharing that online harm had caused suicidal feelings, withdrawn, depressed and many revealing they had changed roles within media to redress their mental health and wellbeing.

● Inconsistency in response by line managers was also highlighted. Many participants praised their managers for offering support. However, some said their managers had failed to support them. Participants also acknowledged the challenging pressure on managers to know how to support their employees during an incident of online harm or a mental health crisis triggered by online harms.

● Multiple participants said that age or references or insinuations about their age was layered into the online abuse.

● There was a sense of resignation from many participants. Several alluded to online harm being perceived as ‘part of the job’ and suggested there was little that could be done when social platforms refused to take action.

Call to action

As a result of this research, Women in Journalism calls for broadcasters, publishers and media organisations in the UK to take action and call for online users to #StopSilencingWomenJournos by pledging the following:

1. To sign-up to(6) or create an online harms policy designed to support all staff, including freelancers and those on temporary contracts.

2. To identify a permanent staff member to act as a champion or leader in connection to online harms.

Support by Women in Journalism

To support organisations with establishing and implementing an online harms policy, Women in Journalism pledges to establish the following:

Creation of a pledge page on the Women in Journalism website, which will offer:

1. A policy to which partner organisations can directly sign-up to 2. A policy template which organisations can choose to download and adapt for in-house application

3. A list of up-to-date, free-to-use, reliable resources which organisations and freelancers can use to find support in connection to online harms 4. Training opportunities for managers in connection to online harms and connected issues such as mental health and welfare

Women in Journalism will also commit to:

● Lobbying for transparency by social platforms around complaint management and response

● Lobbying for better and more consistent response by police and lawmakers

Questionnaire results

Analysis was based on 403 responses:

● 97.9% of respondents were female

● 1.4% preferred to self-describe

● 0.7% identified as non-binary

Personal situation

While the competition of the questionnaire was anonymous, unless participants chose to leave their details, the initial questions intended to give an impression of the section of industry, level of experience and public exposure of the people taking part in order to explore whether online harms were being felt more keenly in some areas than others.

The majority of participants were permanently employed (Figure 1). However, 60 participants were freelance. See Page 24 for more information about the freelance responses.

Figure 1. Participants’ employment status

More than half of the participants worked for Reach plc, with other respondents working for the BBC, Newsquest, National World, ITV, B2B publications, communications and marketing, the Mail Group, News UK, other national and regional print and digital publishers and broadcasters and with 5% not specifying where they were based.

Almost half of the respondents worked mainly in print and digital publishing (Figure 2), another third were in digital-only publishing. Participants working mainly in print publishing made up 6.7% and broadcast participants were just 5% for television and 2.5% for radio. Participants working mainly in social media were almost 5%.

Figure 2. Participants’ main type of work.

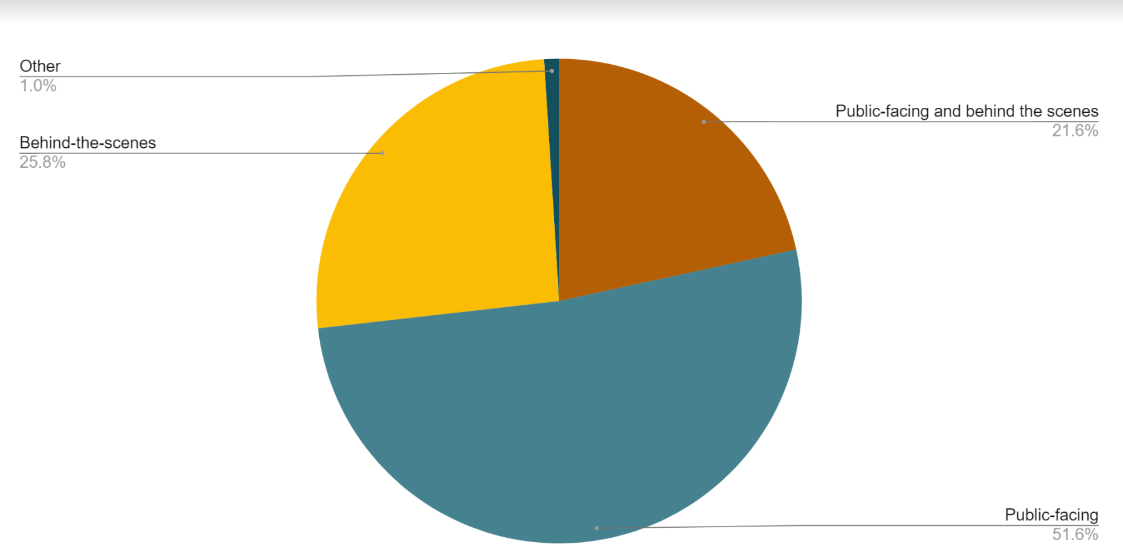

Of those participants, more than half worked in the public eye, with public-facing roles such as presenting, by-lined content or working as an influencer (Figure 3). A quarter worked behind the scenes in roles such as production, editing or research. Just over a fifth worked in a dual public-facing and behind the scenes role. See Page 28 for more information about the impact of the roles on exposure to online harms and impact.

Figure 3. The public visibility of participants

A quarter of participants had worked in journalism or media for more than 21 years (Figure 4). Just under a fifth had worked in journalism for less than two years. While there was no specific question about the age of participants, the length of service is likely to indicate an approximate age of many taking part in the research.

Figure 4. How long participants have worked in journalism or media.

Personal experience

The questionnaire went on to ask participants about their experiences of online harms and safety issues in connection with their work.

Three quarters of participants indicated that they had felt unsafe or threatened at some point during the course of their work (Figure 5). More than a third said they had experienced threats to their safety both online and in the physical world. Another third said they had been made to feel unsafe online and 10% said they had been made to feel physically unsafe.

Figure 5. Perceptions of threat to safety during work

In the past year, almost half of the participants said they had experienced some kind of threat to their safety during the course of their work, with 35% suggesting the threat had been conveyed online (Figure 6). Almost 10% suggested they had received both online and physical threats in the past 12 months. Physical safety threats were fewer (3%), quite possibly because of the increase in remote and home working following the pandemic.

Figure 6. Perceptions of threat to safety during work in the past 12 months

The main categories of harm experienced by participants were intersectional, with many participants indicating they had been exposed to multiple types of harm during the course of their work (Figure 7).

The most common experience was personal comments (60%), followed closely by threats made online or digitally - which was experienced by more than half of participants. Online backlash or pile on had also been experienced by more than half of the participants (51%).

Almost 35% of participants had experienced hate speech or a hate crime and a quarter of respondents had experienced sexual harassment or sexual violence.

Figure 7. Categories of harm experienced overall.

In the past 12 months personal comments remained the most reported event (Figure 8). Online backlash or pile-on was reported second most highly by more than a third of participants (32%). Threats made online (30%) and hate crime (20%) continued to be reported highly by participants.

Figure 8. Categories of harm experienced in the past 12 months

Testimony: threats to safety online and in person

Participants were given the opportunity to share examples of threats to their safety that they had experienced during their course of their work(7). These included:

“The most recent was a catfish account which followed me on Twitter and then sent me sexually explicit direct messages.”

“If I have experienced online abuse where the perpetrator has done a deep dive on my social media and posted screenshots of family member accounts. This included abusive messages about myself and family, leading to a Twitter pile on.”

“Email abuse/harassment over a period of months (including death threats) from a reader. Police were involved but unable to trace them as they were using a secret server.”

“I haven't been threatened but I have felt unsafe on a number of occasions while out working on my own. Some of the areas I have visited for stories have felt unsafe to be alone and I have once been followed while covering a story in a park.”

“After writing an opinion piece online, I was subjected to a heap of abuse. As the story was also posted on bigger publications - people started stalking my personal Facebook as well as my Linkedin, trying to find out information about me. The most they found was finding out where I was born which I was open about - but they started stalking my social media to dig, reacting to my post. Whilst on Twitter, which is the worst for the abuse, many users started tweeting using my name along with personal information. As I am a POC [Person of Colour], they also mentioned my background trying to use it against me.”

“12 years of stalking, court case, destroyed me in every way possible including feeling suicidal.”

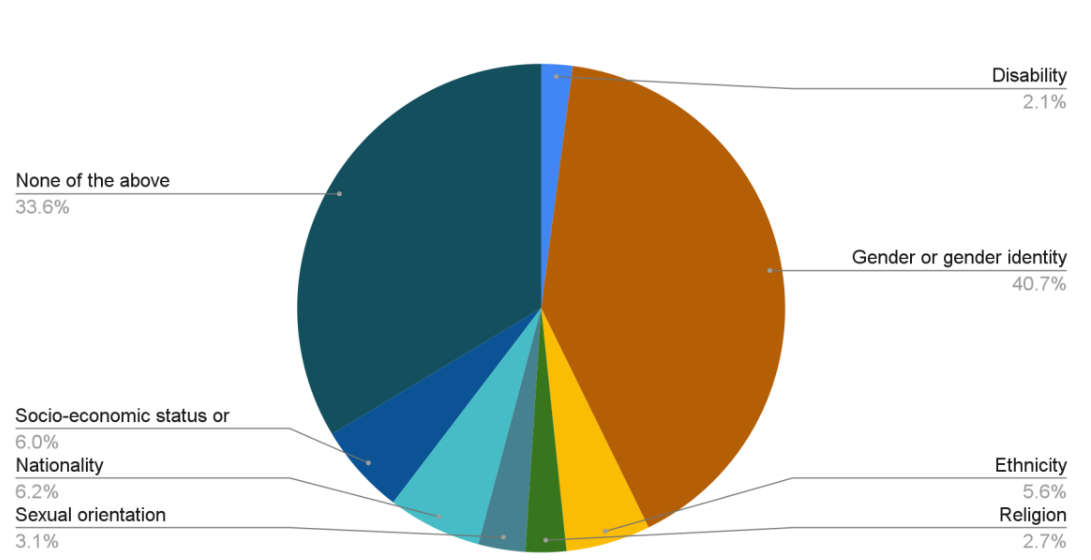

Figure 9. Harms connected to personal characteristics

Almost half of the participants felt some of the harm experienced was connected to gender or gender identity (Figure 9). Ethnicity, nationality and socio-economic status or background were also indicated as a factor in the experiences of online harms along with a small number of participants who suggested sexual orientation, disability and religion were factors.

Testimony: Attacks on personal characteristics

“Many of the insults I did get referred to my race and or gender and dismissed my assessment in the reviews [I was writing] as a result. Saying I was incorrect as clearly I was biased as a WOC [Woman Of Colour]”

“I've been subjected to ill comments with regards to my gender, race, nationality and religion.”

“People constantly make assumptions about me, my economic status, my beliefs and opinions, my intellect and my experience, all because of the way I look. It is exhausting.”

“Often I've seen comments that are homophobic, quite often by people who don't know I'm a lesbian, and I'm not sure if that makes it worse or not- people throwing around bad words- one of which was particularly bad and the system blocked the comment, but on a live you can still see all the comments coming through in real time.”

“As a disability rights journalist I get a lot of hatred for the things I share, people saying I or my community don’t deserve rights or to love, especially in the pandemic.”

Platforms for abuse

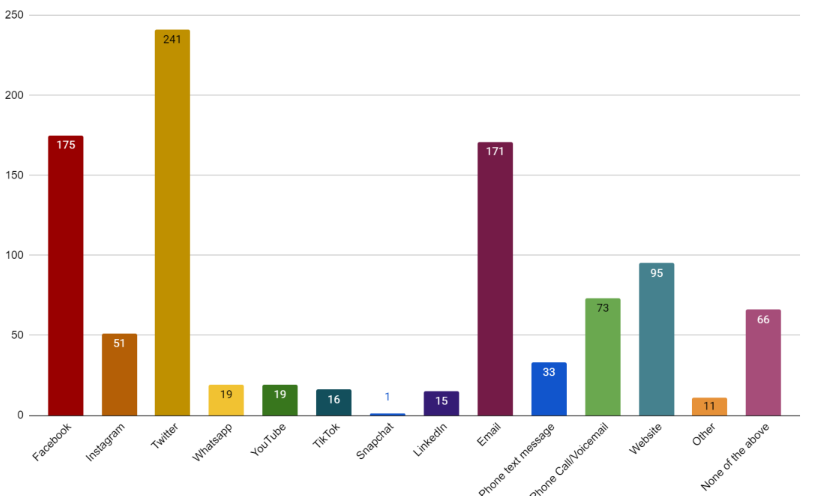

Participants indicated very similar patterns in the platforms for abuse over the course of their careers (Figure 10) and in the past 12 months (Figure 11), with Twitter and Facebook identified by the majority as the major platforms upon which harms were experienced. Email was identified as the third most prolific vehicle for online abuse.

It’s unsurprising that these platforms were the most highly reported due to the high percentage of respondents working on digital platforms and social media (Figure 2) - many of whom likely use the social platforms for promotion of content and whose emails are likely made widely available online.

Instagram was identified as a potentially increasing platform for abuse - with 12% of participants naming it as a vehicle for harm overall, but 12% of the 257 participants who had experienced harm in the past year also identifying it as a platform for harm.

TikTok and YouTube followed similar patterns, again, perhaps unsurprising due to a recent increase in the use of those platforms by mainstream media organisations.

Figure 10. Platforms reported overall

Figure 11. Platforms reported in the past 12 months

Support and response

A third of participants said they had sought support from their line managers if they had experienced online harms (Figure 12). Friends and family members were also used as a support network for a quarter of participants and almost a quarter sought support from colleagues.

However, a third of participants said they had not sought support from any of the suggested options and only 12% said they had sought support from the platform involved.

Just under 10% sought support from the police and just 3% sought legal help. Of those who sought police help, more than half said no action was taken (Figure 13). Almost a fifth said they did not know what the outcomes had been.

Figure 12. Support sought by participants in the event of online harm.

Figure 13. Police response in the event of a report.

Testimony: Police report and response

Clearly, not all online harm should result in police attention, but the testimonies of the journalists who did make a report highlights an inconsistency in response by police and a lack of insight into the outcomes of their reports.

“Police took a statement, and tried to find the harasser, but were unable to as he was using a secret server and was not at last known address. They also offered me safety advice due to the death threats. My local force asked the Met to help, as they thought he might be in London, but they said no.”

“I reported a threat on FB to the police, but the origin was a fake account that had since been deleted (or had blocked me). The police were sympathetic but said they could do nothing.”

“I sent the police screenshots and evidence of the harassment but ultimately nothing was done and this person continues to contact me.”

“I decided against taking action. The man had a history of harassment and breaching orders so feared it would only make things worse.”

“I reported the threatening letter sent to our office to the police. They logged it and told me to keep hold of it, and said if I received anything more they would take fingerprints. That was in November and I've not received anything more.”

“A series of sexually aggressive posts were made about me on a website. The police filed a report and spoke with an individual who was involved. Most effective was my company's lawyer who reached out to the main poster and informed them they were in legal danger and would be sued.”

“I've seen the amount of abuse women experience online, and I have never seen any evidence that either the social media companies or the police take it seriously.”

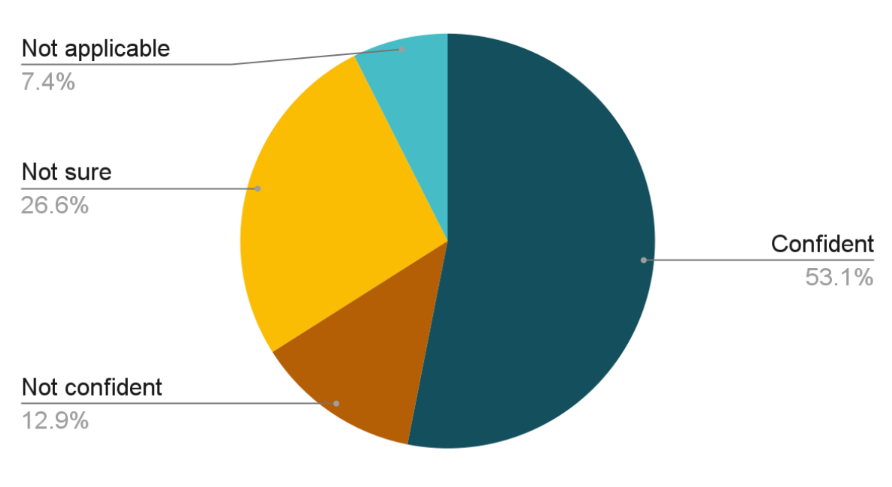

Figure 14. Confidence in company response/support - all participants

More than half the participants said they were confident that their employer would support them in the event of online harms occurring (Figure 14). However, a quarter said they were unsure of the support they could expect to receive and more than 12% said they were not confident in receiving support.

The confidence in employers dropped significantly for freelancers and those on temporary contacts, with only a fifth expressing confidence that they would receive support from their employer (Figure 15).

IMAGE HERE

Figure 15. Confidence in company response/support - freelance and temporary contract participants

IMAGE HERE

Figure 16. Confidence in line manager response/support

The confidence in support from line managers came in at 65% for all responses (Figure 16), but, again, dropped to just a quarter for those just on freelance and temporary contracts (Figure 17). It is worth noting that almost 35% of those respondents said the scenario was not applicable to their situation.

IMAGE HERE

Figure 17. Confidence in line manager response/support - freelance and temporary contract participants

More than half of respondents said they were confident that they would know what to do if they experienced online harm in the future (Figure 18). However, a quarter expressed a lack of confidence and a fifth said they were unsure about their confidence levels.

IMAGE HERE

Figure 18. Confidence in how to take action or find help in the event of online harm in the future

However, almost half of those on freelance or temporary contracts expressed a lack of confidence about how to find support or take action in the future if they were subjected to online harm (Figure 19).

IMAGE HERE

Figure 19. Confidence in what support to seek or action to take - freelance and temporary contract participants

Testimony: Support from companies, managers and confidence in knowing what to do and where to find help in the future

“I often feel there is no real point reporting low level stuff as nothing gets done and there are no real lines of communication for it. I think it is almost expected in this job that you get abuse and it is sort of unwritten that you just accept a lot of it and move on. If it gets out of hand, of course that should be upscaled.”

“I asked my line manager about resilience training for politics journalists, particularly women who were encouraged to promote their work on social media. He was bemused at the idea and said if I wanted to organise it to go ahead.”

“Having been through this process I'm much more confident in reaching out to others for help. When it first happened I thought it was normal (in fact, some colleagues told me it was just the price of being a woman in journalism). But a male boss was a true ally and helped me understand this was not normal and not okay. He got his bosses involved and the main company's legal team, as well as encouraged me to go to the police.

“I would potentially turn to a colleague for support but working remotely, this is more difficult as I do not know my colleagues. Unless the situation was obviously severe, I would not be confident that my line manager would take my concerns seriously if on a lighter scale.”

“Implicit threats have been made from users based in my home country. I work freelance for a client in the UK and am not sure if they would support and protect me like they would their employee.”

“It's unfortunately deemed to be 'part of the job' by editors or superiors.”

The impact of the threat of online harms on participants’ professional practice

More than half of respondents have made some adaptations to their social media use due to the threat of possible online harm, such as changing privacy and safety settings, changed their names or profile pictures and amending notification settings (Figure 20).

Worryingly, almost half said they had decreased promotion of their work online and 10% had asked for their bylines to be removed from their work. A small number (3%) had also asked to not be ‘tagged’ in online promotion of their work.

A quarter of respondents said they were more cautious when working in public spaces and 23% said they were more conscious of their personal safety generally.

Almost a third said they had considered leaving the media industry due to the threat of online harms and 14% said they had considered changing roles. There were four respondents who said they had left the industry due to online harms.

IMAGE HERE

Figure 20. Impact of online harms on participants’ professional practice

Testimony: The impact of the threat of online harms on participants’ professional practice

“I resigned from my job after experiencing a Twitter pile on and didn’t receive immediate support from line manager/colleagues. Support came two days later which, for me, was too late by then.

Now, I am considering leaving the media industry altogether or taking on a role that’s behind the scenes instead.”

“If there is work that I'm aware is on controversial subjects I do not post about it on my Twitter. Otherwise I post all my online work.”

“Online abuse and emails had a terrible effect on my mental health, and I eventually left my job, but remain within the media industry (and in a much better state now!). As I’m part of a team, it’s less about “my content”, however, I am much more cautious about posting my email address online; using a byline next to any written content which can otherwise be avoided; generally choosing “safer” topics to post about on my personal LinkedIn.”

“A major part of my role is to promote our brand on social media. I use professional accounts in the main, to avoid being identified personally and I often find myself not commenting personally on social media to avoid any backlash. But I am definitely more fearful of promoting myself professionally online.”

“I worked for years as a reporter and feature writer but am now in a non-writing role. Applying for this position was not motivated by the desire to have a quieter life/less abuse but I have to say my mental health and stress levels are infinitely better since taking on a less public role.”

“I very deliberately limited my use of social media for fear of abuse. I feel this is detrimental to my career as I see other journalists getting exposure, and promotion, for having large followings. But I don't think the risk to my mental and physical health is worth it.”

Summary and recommendations

Online harm is an interpretive issue and individuals respond differently when faced with online harm depending on a number of factors. However, this report makes it clear that without decisive action to support staff and freelance contributors, there is a real risk that women working in journalism and media will leave their roles or choose to fade into the background online. The research shows the ‘chilling effect’, as identified globally by UNESCO(8), on the voices and activities of women working in journalism and the media is being significantly felt in the UK.

Participants also referred to inconsistencies in how employers, managers and authorities such as the police responded to online harms. In an industry attempting to be more inclusive and with a government attempting to secure a safer internet, the issues highlighted in this report suggest there is still significant work to be done to make online spaces safer for women working in journalism and media.

The comments provided by participants also highlighted a frustration about the lack of accountability of social media platforms but also suggested a sense of resignation - many participants alluded to online harm being ‘part of the job’ and suggested there was little that could be done by individuals when social platforms refused to take action.

There were points made in the responses about physical safety. These will be examined in greater detail and may be used as evidence or a conversation starter for future projects by Women in Journalism.

There was also mention by respondents at times to terminology around language and gender - these points will be shared as a point of reflection and may inform future research design.

The low incidence of women reporting online harm related to their ethnicity or sexual orientation suggests that Women of Colour and women who identify as lesbian, gay or bisexual may have been underrepresented in the survey, as the outcomes did not align with other research findings. A wider response from those working in broadcast and social media would also be valuable in the future, as would a question asking participants their age. Therefore, any future research needs to be shared across alternative networks other than just email, Twitter and LinkedIn.

Sadly, the findings of this report do not suggest we are at a turning point yet in the way online harms against women are managed within media and journalism.

As a result of this report, Women in Journalism calls for broadcasters, publishers and media organisations to to take action, and call for online users to #StopSilencingWomenJournos, by pledging the following:

1. To sign-up to(9) or create an online harms policy designed to support all staff, including freelancers and those on temporary contracts.

2. To identify a permanent staff member to act as a champion or leader in connection to online harms.

Support by Women in Journalism

To support organisations with establishing and implementing an online harms policy, Women in Journalism pledges to establish the following:

Creation of a pledge page on the Women in Journalism website, which will offer: 1. A policy to which partner organisations can directly sign-up to

2. A policy template which organisations can choose to download and adapt for in-house application

3. A list of up-to-date free-to-use, reliable resources which organisations and freelancers can use to find support in connection to online harms.

4. Training opportunities for managers in connection to online harms and connected issues such as mental health and welfare.

Women in Journalism will also commit to:

● Lobbying for transparency by social platforms around complaint management and response

● Lobbying for better and more consistent response by police and lawmakers

Support options

Below is a list of resources available to currently support with online harms and the safety of journalists:

Online safety resources

Communicating with users in distress - Samaritans

Coalition against online violence - response hub

TRFilter - useful to manage harms and build a report of online abuse on Twitter* The Dart Center trauma resources

National Union of Journalists - safety toolkit

Social Media Platforms

Meta safety for journalists

Twitter help centre

TikTok user safety

Acknowledgements

Thanks to everyone who shared, amplified or supported this research in some way. Thanks too to the journalists and media workers who took part and who shared their insights and experiences to inform this report and the recommendations.

For more information about the report please email:

rebecca.whittington@reachplc.com

Appendix

1 The term ‘online harm’ refers to abuse, harassment, doxxing, stalking, threats, impersonation, backlash/pile-on, smears, personal comments, hate-speech, sexual advances/sexual violence, suicidal/self-harm communications and other malicious or harmful communications conducted via digital tools or in an online space.

2 https://pressgazette.co.uk/news/journalists-mental-health-abuse-newsroom/

3 https://en.unesco.org/publications/thechilling

4 https://www.nuj.org.uk/resource/nuj-safety-report-2020.html

5 https://www.nuj.org.uk/advice/journalists-safety-toolkit.html

6 See point 1. Of the Women in Journalism pledge

7 Testimony throughout the report may have been edited to protect participant identity or for context.

8 UNESCO report: https://en.unesco.org/publications/thechilling

9 See point 1. Of the Women in Journalism pledge